Affective Dimensions in Word Embeddings

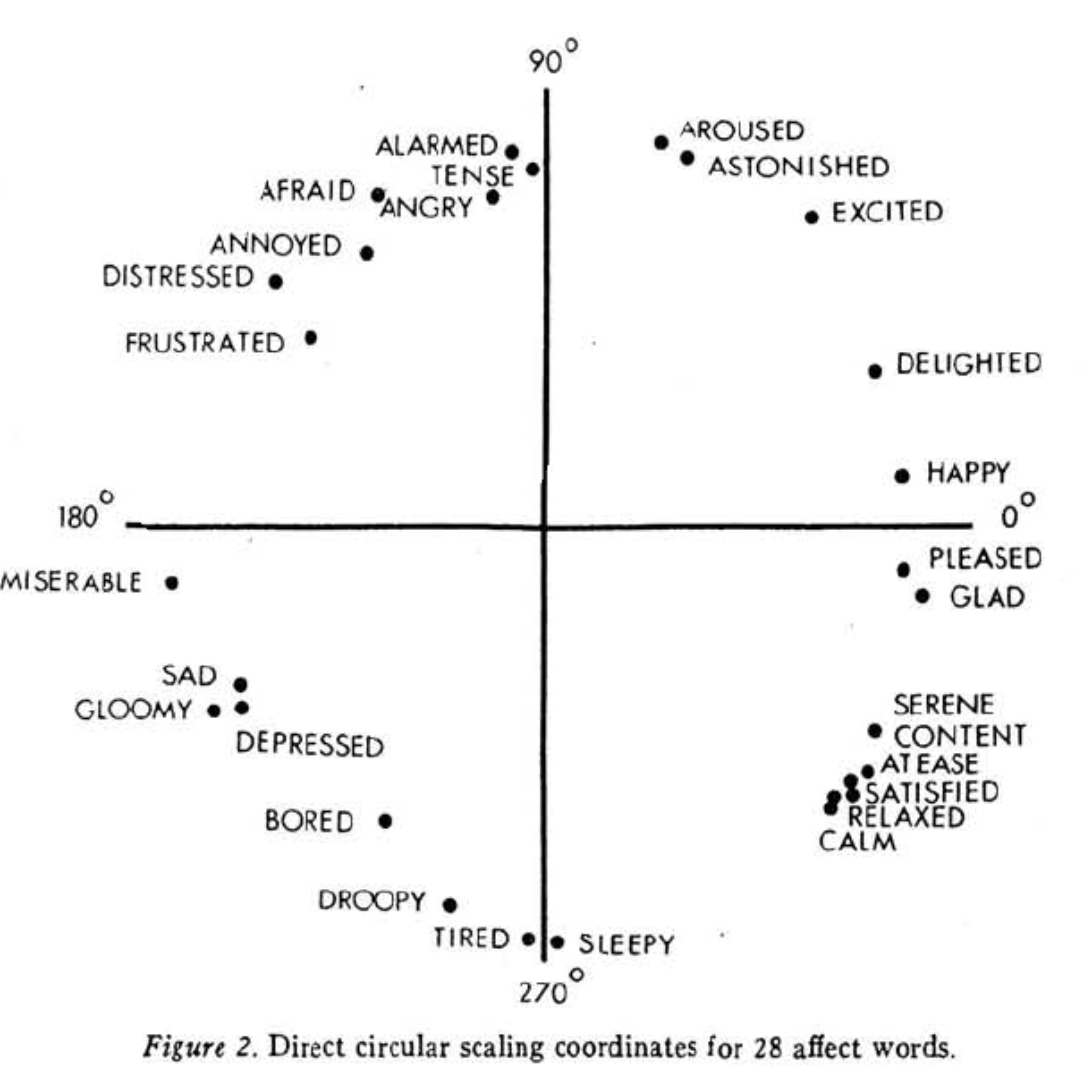

In 1980, psychologist John Russell asked 36 university students to categorize how 28 particular affects -- a term used by psychologists encompassing feelings, moods, and emotions -- made them feel (Russel 1980). In analyzing the results he found that the responses were consistent with the theoretical circumplex model of affect:

Previous studies told Russell that the axes of the circumplex captured a significant portion of how people distinguished between affects. The horizontal axis is valence, which describes if an affective experience is positive or negative. The vertical axis is arousal: here, that's a subjective measure of the energizing or pacifying effect of an affect, but in other studies it's measured as the relative activity of the sympathetic nervous system.

What's amazing about this model is that it's been independently verified and seems to hold across languages and cultures (Posner et al. 2005, Russel 1983, Loizou and Karageorghis 2015). So while all models are wrong, this model at least seems to be consistent with how the average person conceptualizes emotional states. And that's true even if they're not consciously aware of the fact that they have a conceptualization at all!

Which makes me wonder: if valence and arousal are so universal, they must be implicit in our writing. Have large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT picked up on the pattern? Not to say that ChatGPT experiences affective states (you can't understand the experience of arousal without a sympathetic nervous system), but the underlying model might have a latent representation consistent with ours.

Let's find out.

Before we do, I want to clarify the point of this experiment. First, I'm not interested in what ChatGPT has to say about affective states: if you ask you'll get definitions and assurances that the model doesn't "feel", not trustworthy explanations about what happens under the hood.

Second, there are absolutely emotional patterns in natural language to be found. Computer-aided analysis of text goes back to the 60s (Stone et al. 1966), and the early 2000s saw many similar techniques used to predict the emotional content of text (Turney 2002, Pang et al. 2002, Snyder and Barzilay 2007).

But modern LLMs aren't trained on those patterns. They're trained to predict the next word in a sequence, and later fine-tuned for things like "being helpful".

What I want to know is if LLMs, while being trained to predict something else entirely, have somehow encoded valence and arousal in their latent states.

To see if that's the case we'll look at word embeddings, which map bits of text to the state that LLMs use to compute what to say next. Embedding models are often trained jointly with LLMs, but word embeddings themselves pre-date the current wave of LLM-based AI research by several decades.

The word2vec model (Mikolov et al. 2013) made headlines when it was published in 2013 because it let us use math on words to do things like make analogies. For instance, the analogy Einstein : scientist :: Messi : ? could be solved by calculating:

scientist - Einstein + Messi

and finding the nearest vector -- in this case, midfielder.

For this experiment I'll use OpenAI's text-embedding-3-small model to embed Russell's 28 affects; it's cheap and fast and has seen orders of magnitude more data than word2vec. We'll see if there's any relation with the circumplex model of affect, and if there is we'll train a simple model to predict the valence and arousal of other words.

One problem: Russell only includes precise measurements for a handful of the 28 affects. To get the rest, I imported the figure into some photo-editing software and measure the angles myself. My results matched those Russell reports to within a degree -- perhaps surprising, considering the imprecision (or maybe it's just character) of what is clearly a hand-drawn figure.

Here's the cleaned-up version of the circumplex. Hover over any of the data points to see more information.

Graphical Gut Check

Our first step is to look at the data and see if word embeddings have anything to do with the circumplex. And if we apply the lesson of Anscombe's quartet the best way to look at the data is to look at it.

But word embeddings are way too high-dimensional to graph. Even using our small embedding model converts each word to a vector with 1,536 components. If your screen is anything like mine, you've only got two meaningful dimensions to work with, so we need a way to distill those 1,000+ dimensions down to two without losing too much information. One way to do that is manifold learning.

A manifold is anything that "looks like" Euclidean space. If we can find a two-dimensional manifold embedded in our 1,536-dimensional space that touches all our data, we can throw away those other dimensions and flatten the manifold into a two-dimensional graph.

We'll use a technique called t-SNE from van der Maaten and Hinton 2008 to get a manifold that we can graph. t-SNE does what it can to keep nearby vectors close in the two-dimensional projection. Although there's no meaningful interpretation to the precise distances, the distance preservation helps preserve structure. If you want to build more intuition on how to interpret the results of t-SNE see the examples at Wattenberg et al. 2016.

Because we care about the affective dimensions, I've marked every point with an arrow whose angle matches the emotion's position in the circumplex. It looks like the arrows define a locally-smooth field, with a few jumps. That's a good sign for us -- the t-SNE algorithm doesn't know anything about valence or arousal, so this structure is a strong indication that the embeddings carry some amount of information about the affective dimensions.

Predicting Affective Dimensions

Now that we're convinced the embeddings contain some amount of the signal we want, the next step is to build a model to extract it. The main roadblock we'll have to work around is our limited amount of data (remember, we only have 28 data points to learn from) and the huge amount of information available in each embedding. Even a simple linear model is likely to overfit to our dataset, which won't serve us well when we want to get the valence and arousal of other concepts.

Dimensionality reduction won't help us much. Our t-SNE reduction to two dimensions can't handle new data points (we'd have to re-learn the manifold so that it also includes the new data). And embedding models take good advantage of all available dimensions, so tools like principle component analysis (PCA) won't reduce the dimensionality without throwing away a huge amount of information.

Instead we'll fight over-fitting with regularization: we'll add constraints to a simple linear model so that it isn't flexible enough to overfit. For linear models, the standard regularization strategies are Lasso and Ridge. Since Lasso regularization tries to make as many parameters 0 as possible, we shouldn't expect it to take good advantage of how embeddings "spread out" their information, so that leaves Ridge.

I trained independent Ridge models to predict valence and arousal from word embeddings. The models fit well but not perfectly (valence R squared was 0.93, arousal R squared was 0.89), and I've plotted the predicted valence/arousal of Russell's 28 affects below. Click any of the data points to see where the affect was originally on the circumplex.

Since the two models are independent and we're not trying to constrain predictions to be on the perimeter, most affects are inside the circle. This might be a mistake! But I don't know how significant it is: the circumplex model assumes valence and arousal are correlated, but the relation is variable (Kuppens et al. 2013) and might depend on cultural contexts (Yik et al. 2023).

Out of Domain

Normally, to test the quality of a model we would evaluate its performance on a set of data it hasn't seen. But as I only have quantitative data on the 28 affects from Russell's 1980 paper we'll have to rely on a qualitative analysis. Here's what happens when we apply the two Ridge models to a new set of affects:

These affects are given in a worksheet from the Hoffman Institute. I can't speak to the efficacy of the Hoffman process, but the categories and nuance of individual affects give us multiple scales by which to explore the data. Click any of the categories in the legend to filter the dataset.

There are no objective measurements of correctness we can apply here. My sense is that the categories are placed roughly correctly within the circumplex, but it's easy to find pairs whose relative position is hard to justify. I encourage you to explore the dataset and see the quality of the relative valence and arousal values for yourself.

Takeaways

Our analysis is limited by a lack of data, but there is clearly some signal about the affective dimensions in embeddings from OpenAI's text-embedding-3-small model. The R squared scores and casual analysis of the Hoffman Institute affects suggest valence is a stronger signal than arousal. That may just be noise, but it might also be indicative of some structure in English where synonyms have less variable valence than arousal. Without more data we can't readily confirm that hypothesis.

We might also have more success with different embedding strategies. For this experiment I embedded affect words directly and without any other context, but we might also embed a definition or example usage or bit of prose that captures what it means to feel that affect. And if we don't limit ourselves to text and use multi-modal embeddings we might get even stronger signals: Cowen and Keltner 2017 found a high-dimensional emotional structure in self-reported responses to videos (you can explore the data here).

Finally, if we wanted to move beyond embeddings and had compute to spare, we could also apply modern "mind mapping" techniques that look at neuron activation patterns and attempt to map them to concepts (OpenAI 2024, Anthropic 2024). It's likely that some of the activation patterns correspond to our affective dimensions.

If you want to run these experiments for yourself, the source is available here.